Harvard University designs New Textile that which can bolster Speed.

Researchers from Harvard University has developed a textile that can dimple like a golf ball and change its aerodynamic properties on demand. The research results have opened avenues to new, wearable smart materials with applications in sports and engineering.

Its not so far, that when a marathoner; a skier; a cyclist; a hiker can boost their speed by just pulling or stretching their attire – albeit the fabric which is crafted for comfort.

Led by David Farrell, a new type of textile that uses dimpling to adjust its aerodynamic properties while worn on the body. The research has potential to change not only high-speed sports, but also industries like aerospace, maritime, and civil engineering.

Farrell, whose research interests lie at the intersection of fluid dynamics and artificially engineered materials, or metamaterials, led the creation of a unique textile that forms dimples on its surface when stretched, even when tightly fitted around a person’s body. The fabrics utilise the same aerodynamic principles as a golf ball, whose dimpled surface causes a ball to fly further by using turbulence to reduce drag. Because the fabric is soft and elastic, it can move and stretch to change the size and shape of the dimples on demand.

Adjusting dimple sizes can make the fabric perform better in certain wind speeds by reducing drag by up to 20%, according to the researchers’ experiments using a wind tunnel.

“By performing 3,000 simulations, we were able to explore thousands of dimpling patterns”, Farrell said. “We were able to tune how big the dimple is, as well as its form. When we put these patterns back in the wind tunnel, we find that certain patterns and dimples are optimized for specific wind-speed regions”.

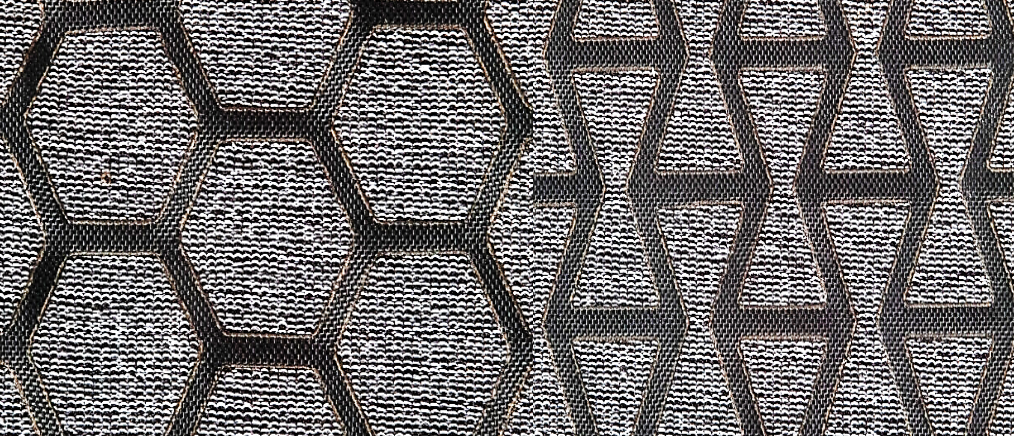

Farrell and team used a laser cutter and heat press to create a dual-toned fabric made of a stiffer black woven material, similar to a backpack strap, and a gray softer knit that’s flexible and comfortable. Using a two-step manufacturing process, they cut patterns into the woven fabric and sealed it together with the knit layer to form a textile composite. Experimenting with multiple flat samples patterned in lattices like squares and hexagons, they systematically explored how different tessellations affect the mechanical response of each textile material.

The textile composite’s on-demand dimpling is the result of a lattice pattern that Bertoldi and others have previously explored for its unusual properties. Stretch a traditional textile onto the body, and it will smooth out and tighten. “Our textile composite breaks that rule”, Farrell explained. “The unique lattice pattern allows the textile to expand around the arm rather than clamp down. We’re using this unique property that Bertoldi – a professor of Applied Mechanics and others have explored for the last 10 years in metamaterials, and we’re putting it into wearables in a way that no one’s really seen before”, Farrell said.

Static aerodynamic surfaces are inherently limited in their ability to adapt to dynamic velocity profiles or environmental changes, restricting their performance under variable operating conditions. This challenge is particularly pronounced in high-speed competitive sports, such as cycling and downhill skiing, where the properties of a static textile surface are mismatched with highly dynamic wind-speed profiles.

Here, the research team have introduced a textile metamaterial that is capable of variable aerodynamic profiles through a stretch-induced dimpling mechanism, even when tightly conformed to a body or object. Wind-tunnel experiments are used to characterise the variable aerodynamic performance of the dimpling mechanism, while Finite Element (FE) simulations efficiently characterize the design space to identify optimal textile metamaterial architectures.

By controlling dimple size, the aerodynamic performance of the textile can be tailored for specific wind-speed ranges, resulting in an ability to modulate drag force at target wind-speeds by up to 20%. Furthermore, the potential for active control of a textiles’ aerodynamic properties is demonstrated, in which controlled stretching allows the textile to sustain optimal performance across a dynamic wind-speed profile. These findings establish a new approach to aerodynamic metamaterials, with surface dimpling and thus variable fluid-dynamic properties offering transformative applications for wearables, as well as broader opportunities for aerospace, maritime, and civil engineering systems.

A textile metamaterial is a class of textile that combines a stiff woven with a stretchable knit. For the work described in this paper, we sourced two textiles, a nylon woven (70 denier from Seattle Fabrics) and a compliant spandex knit (custom circular knit from New Balance). The nylon woven was selected for its high stiffness and fine yarn count (70 D.), which keep the fiber scale below the laser-cut feature size; additionally, the pre-applied thermal adhesive was an added benefit for ease of manufacturing.

The spandex knit was chosen for its stretch, durability, and nearly isotropic mechanical response. Textile metamaterial samples are fabricated in a two-step process that requires only the use of a laser cutter and a heat-press. First, we use the Versa Laser Cutter (Universal Lasers VLS6.60) to cut both textiles to the correct dimensions, for the woven material we also cut a given lattice pattern, such as hexagonal or triangular lattice. The laser cutter parameters were calibrated for textile cutting, which required reduced laser power and reduced cutting speed.

For the case of the woven structure, during the laser cutting process a unit-cell lattice is cut into the woven in a subtractive manufacturing process. Due to innate length scale of the yarn structure, there is a limitation on the width of the woven ligament. For the current study, the unit-cells were limited to a ligament width of 2.25mm. The two textile layers are then glued via a thermally activated adhesive between the layers. In the case of our nylon woven, a thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) coating came pre-applied to the textile without the need for additional processing. The two layers were then combined using a Geo-Knight DK20SP heat-press, set to 180 °C and a pressure of 90 psi. Samples

were pressed for 25 seconds, before being rotated and pressed again. The rotation ensured even pressure distribution from the heat-press during the bonding process.

In the case of cylindrical textile metamaterial samples, a third manufacturing step was required to create cylindrical geometries. Samples were fabricated and bonded in a rectangular form that matched the height and circumferences of the testing cylinder. The thickness of the composite textile, approximately ≈ 0.65 mm, was considered to ensure that the tangential strain was zero when fitted onto the cylinder. The textile was then formed into a cylinder and sewn using a ActiveSeam flat overlock stitch on a Merrow MB4DFO 2.0 machine. This stitch is flat and stretchable along the axial direction while remaining stiff in the circumferential direction of the cylinder.

During textile aerodynamic characterisation, the stitch of each textile cylinder was placed in the down-stream direction to avoid direct interaction with the fluid flow. Two types of wind-tunnel experiments were conducted on textile samples.

Firstly, the textile metamaterial dimpling was characterized through methodical testing and post processing, and secondly, a dynamic profile test was conducted to demonstrate the ability to active change aerodynamic properties into local optimums.

For textile aerodynamic characterisation, wind-tunnel testing was conducted on each sample for 12 uniaxial stretch values, from 0% to 10% strain. When reported in the main text, these 12 strain values were down-sampled to 7 values for presentation purposes. The full 12-sample aerodynamic results have been provided in the Zenodo repository.

During the testing each strain value was tested at 21 speeds between approximately 6.9 and 28.8 m/s (with an approximate increment of ∆U ≈ 1m/s). After each sample point, the wind-tunnel was ramped up to the subsequent point and given 25 seconds to allow the air flow to stabilize, after which 30 seconds of aerodynamic data (air velocity and force transducer data) was collected and averaged.

During the dynamic profile test, a velocity profile was generated based on approximate speeds experienced in high-speed sports such as downhill skiing and cycling. This 10-minute profile was tested on four textile states: ε = 0%, ε = 5%, ε = 10%, and a dynamic stretching test what switched between ε = 5% and ε = 10%.

For the dynamic stretching test, to avoid spikes in the drag force data, the data collection was stopped

for 40 seconds to dynamically change the stretch on the textile structure. All results were then compared to the ε = 0% condition and the percent change in the drag force was calculated.

To post-processing the aerodynamic data, a Gaussian low-pass filter was initially applied to remove high-frequency noise. Subsequently, the data underwent smoothing using a Savitzky-Golay filter, selecting a window-size of 10,000 samples, which corresponds to 8.3% of the total data. This approach helped to maintain the integrity of the underlying aerodynamic trend while reducing noise. The residuals of this smoothing process, denoted as ri, are computed as follows:

ri = fi − ˆfi, where fi is the aerodynamic drag at a specific time-point, and ˆfi is the force value

smoothed by the Savitzky-Golay filter. The standard deviation of these residuals, representing the variability around the smoothed values, is calculated as: σresidual = std(ri).

Team Maverick.

France Persuading China In Helping Ending The Ukrainian War.

Brussels; December 2025: French President Emmanuel Macron concluded his trip to China wher…