Indian Government’s Trade Agenda Runs In The Opposite Direction Of The Apex Court’s Ruling Over Tiger Global Diplomacy.

February 2026: On 15th January 2026, India’s Supreme Court has ruled that US investment firm Tiger Global must pay tax in India on the sale of its stake in e-commerce giant Flipkart to Walmart in 2018. The 152-page judgment overturned a 2024 Delhi high court decision that had allowed Tiger Global to claim tax relief under the decades old India–Mauritius tax treaty.

The ruling, which could reshape how foreign investors exit their Indian investments, sets out a tougher interpretation of tax treaties. It allows authorities to deny treaty benefits if offshore investment structures are deemed to be sham entities with little commercial substance – even when investors hold valid documentation. The judgement gives India wide powers to scrutinise any offshore corporate deal. But experts warn it could unsettle international investors and hurt business sentiment.

According to a large section of the legal fraternity, the ruling could lead to scrutiny of old transactions and share sales long thought to be settled. On the other side, other acquiescent reiterated that the judgment opens up unjustifiable windows for tax authorities to scrutinise any offshore corporate deal. This can undermine policy stability and certainty, which are critical for doing business in India.

The Tiger Global case dates to 2018, when US retail giant Walmart bought Flipkart in one of the largest e-commerce deals of the time. Tiger Global, which invested through 03 Mauritius-based entities, sold its entire 17% stake for about $1.6bn (£1.19bn). The transaction initially drew attention as a landmark foreign exit from India’s e-commerce sector, before becoming one of the country’s most closely watched tax disputes.

The 15th January Supreme Court’s decision stands in sharp contrast to the government’s economic agenda. In 2019, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had slashed corporate tax rates, sacrificing public revenue even as companies nearly quadrupled their profits, wages stagnated, and private investment flatlined. Rather than change course, the government has doubled down.

The Tiger Global ruling comes at a moment when fiscal ground rules are more important than ever but are increasingly under threat. In recent years, India’s digital economy has expanded rapidly, powered by the Unified Payments Interface (UPI), which was launched a decade ago and is now the world’s largest real-time payment system. The resulting “instant commerce” boom has generated sharply rising revenues for global giants like Amazon and Walmart, whose business models rely on intense competition to deliver goods in under ten minutes, often at the expense of delivery workers.

Despite their growing revenues, these companies pay little or no tax in India by reporting losses instead of profits from their local operations. Their tax avoidance strategies were reinforced by a 2025 Delhi High Court ruling that payments to foreign cloud-service providers are not considered royalties or fees for technical services under Indian tax law or the India-US Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement (DTAA).

Tiger Global had argued that its gains were shielded from Indian tax because the investment was held through entities in Mauritius, invoking a long-standing tax treaty between the two countries. It relied on tax residency certificates issued by Mauritius, which had traditionally been accepted as sufficient proof to claim treaty benefits. India under the aegis of Narendra Modi had changed tax rules in 2016, making gains from the sale of Indian shares taxable even under treaties. Investments made before 01st April 2017, however, were exempted. Tiger Global said its Flipkart investments predated the change and, therefore, qualified for the exemption.

On the contrary, Indian tax authorities rejected the claim and argued that the Mauritian firms served as conduits and were used only to avoid taxes, with no real business purpose. The Supreme Court has now sided with Indian officials, ruling that tax certificates alone do not guarantee treaty benefits and that the investment structure lacked real commercial substance. It held that foreign investors cannot rely on complex offshore set-ups when those entities don’t carry out genuine business activities of their own.

Indian Tax Authorities have tightened withholding rules under the Income Tax Act, introduced levies on digital services, and adjusted the Goods and Services Tax framework to cover cross-border digital transactions. But these efforts have been undermined by the government’s latest budget, announced on 01st February 2026, which grants generous long-term tax incentives to global cloud providers, including a 20-year tax holiday for data centers, and offers greater “transfer pricing certainty” to tech-driven firms.

Against this backdrop, the dispute between India’s tax authorities and Tiger Global, one of the world’s most aggressive hedge funds, illustrates how multinationals use complex legal structures to minimise their tax liabilities. Between 2011 and 2015, Tiger Global had acquired shares in Flipkart’s Singapore holding company, which held stakes in multiple Indian companies. In turn in 2018, when Tiger Global sold those shares to Walmart, it claimed exemption from capital gains tax under the India-Mauritius DTAA. Indian tax authorities challenged the claim, and after a years-long legal battle that included multiple lower-court decisions, ultimately prevailed.

The original 1982 India-Mauritius tax treaty had long been exploited by foreign companies engaged in so-called “treaty shopping”. For over two decades, more than $171 billion in foreign investment flowed into India via Mauritius, largely for tax reasons. This led to a renegotiation of the agreement in 2016, which granted authorities the right to tax shares acquired after April 2017. Since then, Singapore has largely replaced Mauritius as the preferred financial gateway into the Indian market.

Applying this revised framework, the Supreme Court held that the Mauritius entities used by Tiger Global were mere conduits, lacking any genuine commercial purpose beyond extracting value from India and shifting profits to low-tax jurisdictions. The Court rejected the argument that a Mauritian tax residency certificate alone entitled the firm to tax exemptions. Instead, it declared the transaction “an impermissible tax avoidance arrangement” and affirmed that “taxing income arising from within its own borders is an inherent sovereign right of a country”.

The Court’s decision, which could leave Tiger Global with a $1.5 billion tax bill including penalties, sends a powerful message: companies doing actual business in India have nothing to fear, but those routing investments purely to dodge taxes will face serious financial and reputational costs.

JB Pardiwala, one of the two judges, wrote: “Taxing an income arising out of its own country is an inherent sovereign right. Any dilution of this is a threat to a nation’s long-term interest”. The exact tax and penalty bill for Tiger Global depends on its profit from the deal and is not yet known.

The ruling has raised concerns around future sales of investments for private equity funds or foreign direct investment routed through the island nation. It also has wider ramifications since India and Mauritius signed a protocol in 2024 amending their tax treaty to benefit only companies with legitimate businesses and not shell companies set up to avoid tax, says Fereshte Sethna, a tax lawyer and senior partner at DMD Advocates. The protocol has yet to come into force and will apply to future deals.

India had long tried to attract foreign capital by encouraging investments from companies with structures in countries such as Mauritius, Singapore and the Netherlands, signing treaties to help investors avoid paying taxes twice. It worked. Between 2000 and March 2025, Mauritius alone accounted for about $180bn (£133.9bn), nearly a quarter of all foreign direct investment into India, according to official figures.

Tax experts say the court has applied the law as it is written, they warn it creates new uncertainty. It challenges the government’s earlier promises to safeguard pre-2017 deals routed through places like Mauritius. If the government promised protection for investments made before 2017, then this ruling could be seen as undoing that promise, says Sethna, who appeared on behalf of Vodafone in India’s longest-running tax litigations in the past decade. India’s battle with the British telecom giant over a $2bn tax claim lasted years and ultimately reshaped how the country taxes cross-border transactions, even prompting a controversial retrospective tax change. Vodafone eventually won the dispute.

The question now is whether Narendra Modi’s government will stand by this sensible outcome or undermine it through new tax concessions. India’s recent trade deals with the European Union offer little cause for optimism. While the full agreements remain under wraps, what has been revealed is troubling. For example, reports suggest that the EU-India trade treaty includes “modern digital trade rules designed to facilitate business”, along with other tax-related measures that may be buried in the fine print.

Then there is the Donald Trump factor. Earlier this year, the Trump administration pressured members of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework to exempt US-based multinationals from the global minimum tax. The US-Indonesia trade deal went even further, forcing the Indonesian government to abandon planned tariffs on cross-border data flows and support the renewal of the World Trade Organization’s moratorium on e-commerce duties.

More broadly, the notion that developing countries must tolerate tax avoidance to attract investment does not withstand scrutiny. Investment decisions are driven primarily by market size, growth prospects, infrastructure quality, and labor skills, not by the availability of tax loopholes. India’s vast consumer market, skilled workforce, and advanced digital infrastructure would make it an attractive destination for foreign companies without shell-company-based tax planning.

Tiger Global is a case in point. India’s digital ecosystem was built by Indian institutions, funded by Indian taxpayers, and sustained by Indian consumers. When Tiger Global realised $1.6 billion in profits from selling its stake in Flipkart, it had monetised publicly built infrastructure and the network effects created by India’s digital transformation.

No treaty loophole should allow foreign investors to profit from India’s infrastructure while contributing nothing to the tax base that sustains it. The Supreme Court has affirmed that principle. It now falls to the Indian government to reinforce it by asserting tax sovereignty rather than diluting it through opaque, exploitative trade deals.

Team Maverick.

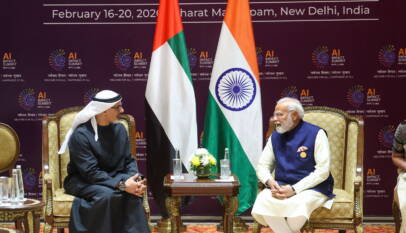

Visit of H.E. Mr. Dick Schoof, Prime Minister of the Netherlands, to India

Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi held a bilateral meeting with H.E. Mr. Dick Schoof, Prim…