Why is a Green Country like Suriname betting its future on oil?

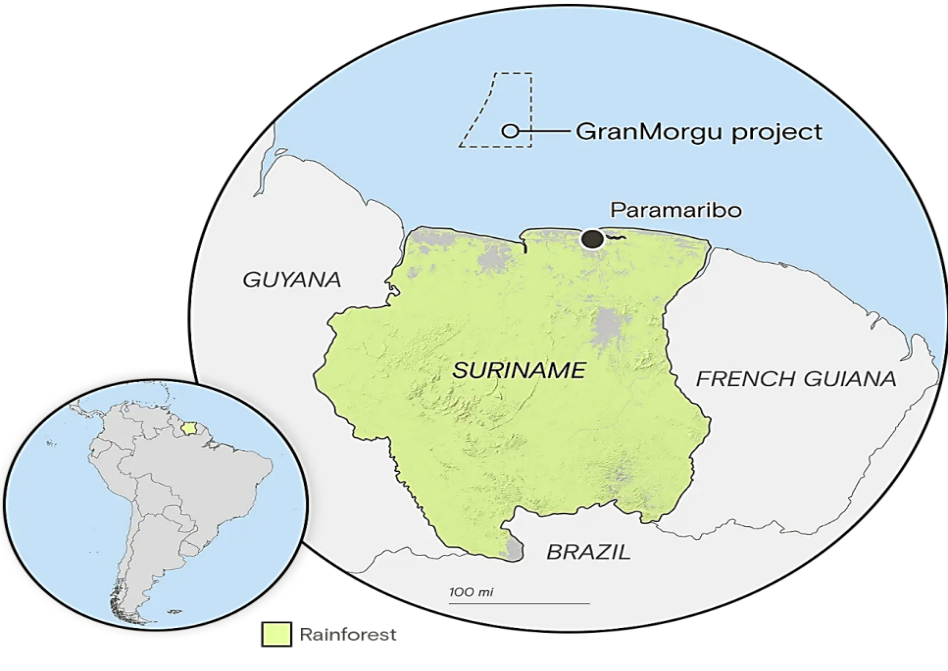

Paramaribo sits on the northeast coast of South American country – Suriname, at the edge of a relatively undisturbed section of the Amazon rainforest. This massive jungle covers more than 90% of Suriname’s landmass, making it the world’s most forested country by percentage. It also allows Suriname to claim itself as “carbon-negative”, meaning that the nation absorbs more greenhouse gases than it emits.

Suriname is one of the few countries that can make an unimpeachable claim to being on the right side of the climate crisis. But all that is about to change.

In 2028, the country’s first offshore oil platform will begin pumping almost a quarter-million barrels of crude each day, roughly enough to supply the daily needs of all the drivers in the state of Colorado. In its first year alone, this project from the French oil major Total Energies is expected to generate billions of dollars of revenue for the government and billions more in private spending, causing the country’s economy to grow by more than half. More offshore rigs are expected to follow.

Shell authorities have praised the emergence of a “balanced energy transition” approach, while those from development banks and market analysis firms spoke about a new emphasis on “energy addition”, rather than “transition”. As the attendees saw it, there was nothing odd about the spectacle of a carbon-negative country hosting a celebration of new oil extraction, amid damaging floods only likely to become more frequent with more global warming.

From one perspective, the commissioning of Suriname’s oil industry is a retelling of a familiar story: A massive oil company wins over a country with the promise of riches, enlisting it in an effort to produce more of a commodity that is destroying the world. But from another, it’s the story of a country seeking to balance its economic growth with the welfare of the planet, in the absence of global infrastructure to help it develop in other ways.

As of date, Suriname’s coveted “carbon-negative” status has been inextricably linked to its underdevelopment. Its slice of the Amazon sequesters more carbon than the country can emit only because its citizens by and large cannot afford the energy-intensive lifestyles that much of the world takes for granted. The average resident earned less than $500 per month in 2024.

Now, Suriname’s leaders want to alleviate that poverty without becoming a net source of carbon. The plan is not just to make money and employ people, but also to use oil as a financing mechanism to build an economy that will someday become independent of fossil fuels, according to senior government officials who have served across the country’s recent administrations. This means a host of new infrastructure projects and social welfare programs that check the boxes of sustainable development: Suriname will seed green industries such as ecotourism and climate-smart agriculture, build mangrove sea barriers and storm-drain systems to stop flooding, and transition away from the use of imported bunker fuel and toward solar and hydropower.

But it also means allowing Total, the world’s sixth-largest oil company by market capitalisation, to pump around 750 million new barrels of oil, more than will come from a massive oil development such as Conoco Phillips’s Willow project in Alaska. And that’s the bare minimum, assuming that no other multinationals strike crude and drill their own rigs.

Post COVID pandemic, Suriname sank into a debt spiral, the result of excessive household power subsidies and low prices for commodities such as gold that are its main source of export revenue. The country owed around half a billion dollars to China, $ 88 million to the Paris Club, and another half-billion to private bondholders that had lent money to the government to help it prop up public budgets. In 2020, the government defaulted on its sovereign debt, leading the International Monetary Fund to step in with strict curbs on government spending.

But as this debt crisis unfolded, seeming salvation was waiting offshore. In 2015, Exxon Mobil made a major oil discovery off the coast of neighbouring Guyana. Drilling studies soon found that the offshore ridge near Suriname contained billions of barrels’ worth of oil, which is lightweight and easy to extract, in addition to the abundance of natural gas. A half-dozen firms started exploring in Suriname’s water, and in 2021, Total struck oil.

A discovery such as this often leads to disaster through the so-called resource curse: When poor nation become reliant on new fossil fuel revenue, it leaves them vulnerable to global price fluctuations, and their governments sometimes embezzle or misuse oil money rather than sharing it with citizens.

A companion phenomenon, known as ‘Dutch disease’, occurs when a country’s overwhelming focus on one new industry leads to a decline in the rest of its economy, as Suriname’s former coloniser experienced after a gas field discovery in the 20th century. Countries including Cameroon, Guyana, and South Sudan, to name a few, have developed oil projects over the decades that never delivered broad prosperity.

Staatsolie, a public oil company of Suriname, managed to struck a win-win negotiation with Total Energies; Staatsolie insisted on a royalty rate of 6.25%, more than twice what Guyana was able to negotiate, as well as a 36% corporate income tax and a guarantee that Total would hire locals. Staatsolie also secured a $1.6 billion loan from development banks, which allowed it to take a 20% stake in the project. In all, Suriname will get up to 70% of the revenue from Total’s oil.

Last October, Total made its final decision to proceed with the oil project, which the company called Gran Morgu. It is the name of a wide-mouthed fish that is native to Suriname’s offshore waters, but in the unofficial national language of Sranan Tongo, it means “new dawn”. Given the scale of change that the oil project would bring to Suriname, the name seemed more than appropriate.

Suriname’s leaders argue that they have found a way to thread this needle. The country is building out a fossil fuel industry, with two big caveats. First, it is taking every possible step to mitigate emissions from its oil infrastructure while protecting its rainforest. Second, it is only developing oil as a means of building a low-carbon economy and raising the living standards of its citizens. Essentially, Surinamese officials say they are using oil revenue to do the development that rich countries won’t pay for.

During the conference in June, Total authorities had pointed to plans for an offshore rig that will cut down on carbon emissions. The entire rig will be electric, and Total has agreed to reinject almost all natural gas that comes to the surface, flaring it only in emergencies. (Electricity use and gas flaring account for a large share of the emissions associated with getting oil out of the ground.) Suriname’s carbon ledger will technically remain negative overall.

But the centre of this mitigation effort will be the rainforest. Suriname’s relatively pristine Amazon jungle is the source of its carbon-negative status, but new mining and logging developments claim more of it each year. The country has lost about 1.5% of its forest cover since the turn of the century, according to one watchdog group. If left unchecked, deforestation could threaten the country’s carbon-negative status sometime in the next decade. So even as the country sells oil on the global market, it also wants to sell so-called carbon offsets, or monetized guarantees that the forest will stay intact. Many countries and companies purchase these credits on international exchanges in counterbalancing their own emissions.

The carbon offset industry is rife with fraud and negligence, and many offset projects around the world have fallen apart, but most experts anticipate that demand for these offsets will grow over the next few decades. For Suriname, rainforest credits could act as a companion product to barrels of oil, allowing foreign countries to buy both the fuel that they need and a counterweight to that fuel’s emissions. For Suriname, the credits could be a way to replace the financial benefits of destructive sectors such as mining and logging.

Total has offered to buy $50 million of Suriname’s potential carbon credits to appease its climate conscious shareholders, and countries including Japan and Singapore have expressed interest in purchasing credits as well.

In the long term, the government will need to use oil profits to build an economy that plays to Suriname’s other strengths. Government leaders and climate experts in Suriname cite industries like rainforest ecotourism and sustainable agriculture as potential growth areas. Yet again, marketing carbon credits will be a centrepiece of this strategy: If the country can become an ecotourism destination, develop a thriving farm sector, and generate tens of millions of dollars a year through the sale of rainforest offsets, it may not need oil revenue by the middle of the century.

Team Maverick

Andhra Pradesh Releases ₹1,200 Crore to Clear Scholarship and Fee Reimbursement Dues, Boosting Higher Education

In a major step to strengthen higher education and ease financial pressure on students, th…