The Reign of the Bearded Vultures – where Human’s dare.

Each year, as snow and ice melts from the peaks of the Alps, young bearded vultures take their first flights. Fending for themselves for the first time, they look for food — not live prey but the carcasses of ibex and mountain goats that died during the winter, their bodies preserved in the ice. As summer lengthens and the young birds get bigger, their attention shifts to a different food source — bones. Bearded vultures are the only animal with a diet of almost all bone.

But a century ago, these vultures would not have been seen along the European mountain range. The local population was driven extinct, as bounties were placed on their heads, since people believed they snatched and killed lambs and even small children. The last wild bearded vulture in the Alps was shot and killed in the Aosta Valley in Italy in 1913. But, a reintroduction project, led by the Vulture Conservation Foundation (VCF), populations are now rebounding. In 1986, VCF started releasing vultures raised in captivity into the wild, and since then it has released 264 birds in the Alps. The alpine population is now self-sustaining, with 522 wild fledglings born since 1997. The birds were declared a protected species by the EU in 2009, and in France, hunting one carries a maximum penalty of €150,000 ($206,000) along with a rigorous imprisonment of three years.

Today, VCF estimates there are up to 460 bearded vultures in the Alps, with 61 wild birds born in 2024. Where once farmers hunted the “gypaète barbu” or “lammergeier” as they are known in French and German, now hikers turn their eyes skyward, hoping to catch a glimpse of these birds that came back from the brink.

Bearded vultures have a wing span up to 2.85 meters (9.3 feet) allowing them to hunt over 700 kilometers (435 miles) in a day. The feathers on their neck, head and torso are naturally white, but they dye them orange by covering themselves in the iron oxide-rich mud found in the mountains and highlands where they live. However, their name comes from the distinctive black tuft of feathers under their beak. These vultures are scavengers, and up to 85% of their diet is bone. Historically, they were called “ossifrage”, derived from the Latin for “bone breaker”. They mostly swallow bones whole, their strong stomach acid breaking them down, but if a bone is too big, they will drop it from height onto a rock to break it and expose the nutrient rich marrow inside.

While Alpine farmers no longer blame the vultures for missing sheep, or children, the birds are still threatened. Accidental poisoning through eating animal carcasses containing drugs, pathogens or steroids, collisions with power lines and wind turbines and habitat degradation have reduced the global population — which spans from western Spain to China — by as much as 29% in the last three generations. Exacerbating this problem is their slow breeding rate. A breeding pair will only lay one or two eggs a year, and even if both hatches, the stronger chick will kill its weaker sibling.

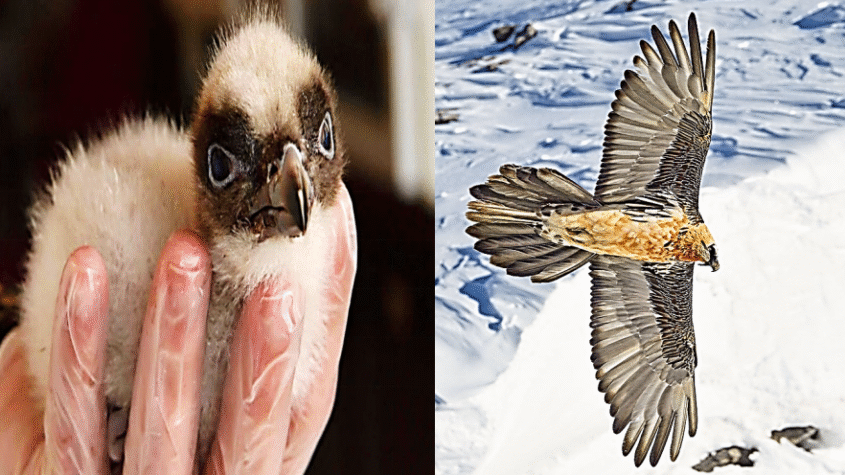

Initial attempts by conservationists to reintroduce the bearded vulture involved capturing birds in Afghanistan and releasing them in the Alps, but the project failed due to the difficulty in capturing and transporting the birds. However, in 1986, three birds that had been raised in captivity at a center in Austria were released successfully in the country’s mountains, leading to a flurry of further releases across the Alps. The young birds are put in artificial nests on cliffs, enabling them to acclimatize to the new environment, and after 20 to 30 days they take their first flight. Young bearded vultures are known for traveling vast distances. In 2020, one bird flew 1,200 kilometers (745 miles) from Haute-Savoie in the French Alps to the Peak District in the north of England. Regardless of how far they roam, when they reach adulthood, they typically return home.

Now that the population is stable, the team have started releasing genetically distinct birds to increase the diversity of the population so “they’re fully equipped to survive, even in a period of climate change”

While releases in the Alps are winding down as the population grows naturally, the VCF is working on “replication and expansion” projects in Valencia and Andalucia in Spain, the Massif Central in France, and the Balkans, as well as possible projects in North Africa.

Another conservation project in the Maloti-Drakensberg mountains of Lesotho and South Africa is working to save the last bearded vultures in the southern hemisphere. The Bearded Vulture Recovery Program did not have a captive breeding program when it started, so instead, when a vulture lays two eggs, the team takes the second egg from the nest, which would be killed by its sibling anyway, and raises the chicks in captivity before releasing them. They are now raising 27 birds in captivity and aim to reach 150 breeding pairs in the wild. With these global conservation efforts, there is hope that bearded vultures will continue to soar across mountains all over the world.

Team Maverick

USA Dominate Netherlands with All-Round Show to Seal Historic T20I Victory

Chennai, Feb 2026 : The United States delivered a commanding all-round performance to crus…