The Fate Of A Shadow Fleet When It Is Sanctioned.

December 2025: On 14th December 2025, a 58,000-ton oil tanker called the Mikati was sailing through the waters of the Indian Ocean, when it received some news from faraway Brussels: it had been added to a list of sanctioned vessels in Russia’s shadow fleet.

The story of the Mikati, currently passing through the English Channel, illustrates the strengths and weaknesses of the European Union sanctions regime that now includes some 600 ships. The EU had listed the Mikati in July 2025, following a similar decision by Britain in November 2024. Built in 2003, its advanced age makes it a typical shadow fleet vessel, as does the behavior that preceded its designation.

According to data provided by Windward, a maritime intelligence company, the Mikati went through a series of name changes, was sold to an anonymous owner, and repeatedly turned off its AIS location transponders in the period before it was sanctioned. These are regarded as “dangerous shipping practices” by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and is only permitted under special circumstances. The Mikati also changed the flag it was registered under, switching to Sierra Leone.

“Sierra Leone’s government outsourced management of its ship registry to a private company based in Cyprus”, Windward analyst Michelle Bockmann told Reporters, adding that the country was “the flag registry of choice” for shadow vessels.

Taken together, these indicators were evidence enough to get the Mikati blacklisted. The EU included the Mikati in its 18th sanctions package against Russia on July 18th. It had an immediate impact. 02 days later, on July 29th, the ship entered the waters off Kochi, home to one of India’s largest oil refineries. But it did not unload the full cargo it had picked up in Russia’s Barents Sea port of Murmansk a month earlier.

It’s not clear if there was a hitch or if the Mikati was following pre-arranged plans. “Sometimes ships are sanctioned when they’re already under way, so someone will have to give the buyer a call and ask if the deal is still on”, Benjamin Hilgenstock, a senior economist at the Kyiv-based KSE institute, told media reporters. “They may be told ‘we need to figure this out first, so maybe wait a bit’, or else, ‘we’ll take your oil but only if you give it to us for a little less money’”, he added.

In any case, something was stirring behind the scenes. On July 25th, the Mikati had changed its registered owner and commercial manager, moving from Azerbaijan to Samoa, a nation of some 200,000 people in the South Pacific not known for having a thriving shipping industry. The company listed, Alga Oceanic Ventures, appears to have no Internet presence.

Its address is a business complex called La Sanalele, where its neighbours have included another shipping manager, Faleola Nexus Ltd, operator of an oil tanker named Orion, which also been sanctioned by Britain and Ukraine for illicit trading in Russian crude. Another neighbour was a Taiwanese company called Pro-Gain Group Corporation that was sanctioned by the United States in 2018 in connection with illegal dealings in North Korean coal and oil.

The Mikati’s sudden ownership switch was followed by a new voyage, north along the coast to Mangalore. There, on August 03rd, it signaled that it had unloaded. “The 11 days delay was probably related to its sanctions and having to get new insurance”, Bockmann said. “That’s a really good example of how EU sanctions are disruptive. But they have very little teeth”.

Indeed, despite sanctions, the Mikati unloaded its oil and stayed in service. Sanctioned vessels can’t visit EU ports or get Western insurance and have trouble finding professional crew. But they maintain the “right of innocent passage” through international waters.

Meanwhile, Kpler, a trade analytics company vide a study conducted in October, had published a report dated 21st October 2025, demonstrating that “Russia has sustained its crude exports despite the logistical challenges posed by the recent escalation of sanctions targeting shadow fleet tonnage”.

Sanctions imposed by the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) were deemed considerably more effective than by the EU. “This data set shows that India is OK with accepting European, and United Kingdom sanctioned vessels, but they don’t want to accept the OFAC sanctioned vessels. And probably this shows that India is a bit more reluctant to find themselves in prospects of secondary sanctions by the US”, Kpler analyst Panagiotis Krontiras informed the reporters,

The Kpler data details reductions in productivity, measured by the fall in kilometres traveled and tons of cargo carried, for ships under each sanction regime. For the US, there was a 70% average decline, for the EU it is only 30%.

EU Sanctions Envoy David O’Sullivan said, that “sanctions are always a bit leaky” and it was always possible to find “examples of a vessel that has nonetheless continued” to operate. But, he added, “our figures show that once a vessel is sanctioned, it drops its ability to carry Russian oil by about 73%”.

Furthermore, while O’Sullivan estimates the EU has now sanctioned two-thirds of Russia’s shadow fleet, OFAC has hit around 40%, according to Kpler data. While the EU has repeatedly added new vessels this year, OFAC has not added any since January.

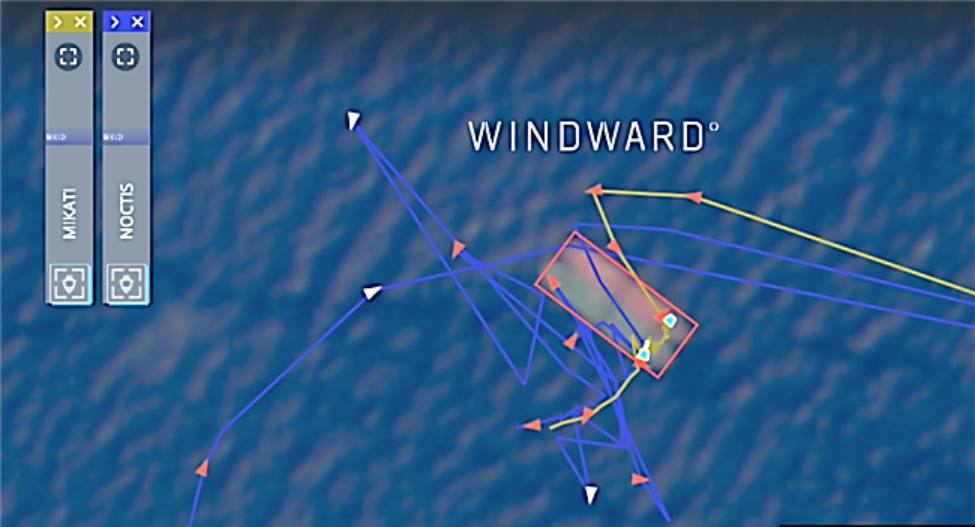

In any case, while the Mikati has continued sailing, it has not been very productive. Windward data shows that after unloading in Mangalore, it sailed through the Suez Canal and anchored at Port Said for a week in August, where it had picked up oil in a ship-to-ship (STS) transfer from another blacklisted tanker, the Noctis. Such transfers are not illegal but are a frequent practice for evading sanctions.

The Mikati took the oil to Ningbo, China, arriving on 29th September, but didn’t discharge it until 15th October. Again, the reason for the delay isn’t clear. Bockmann noted that it “remained loitering around the port area for a protracted period of time, which is part of a pattern of highly uneconomic behaviour”. Again, this is a routine phenomenon of the sanctioned vessels.

“Once you’re sanctioned, you have two choices: either go Russia-India or Russia-China. And that’s why there is this huge productivity drop”, said Kpler analyst Krontiras. An unsanctioned vessel would seek to pick up new cargo somewhere rather than traveling home empty on what is known as a “ballast leg. But now they don’t have this option, they have to go back to Russia, pick up another cargo, and this is a very long ballast leg”, said Krontiras.

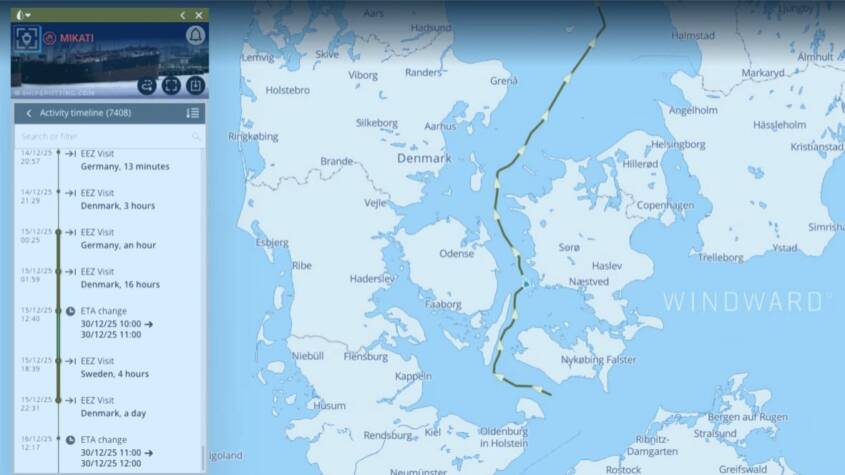

The Mikati did just that. Windward data also shows it once again switched off its transponders between December 10th and 12th, near Russia’s main Baltic crude export port, Uts-Luga. On December 18th, it was heading southwest through the English Channel. “Destination likely India or China, or even STS. No indication”, noted Bockmann.

Team Maverick.

From Playrooms to Prototypes : How an Eight-Year-Old Is Quietly Redefining What It Means to Learn, Build, and Belong in India’s Hardware Future

Hyderabad, Feb 2026 : At a time when India is doubling down on manufacturing, electronics,…