Syrian Refugees Head Home to Uncertainty.

Damascus; December 2025: This coming Monday – 08th December would mark the first anniversary of the ouster of Syria’s Bashar Assad and with it the end of the country’s brutal civil war.

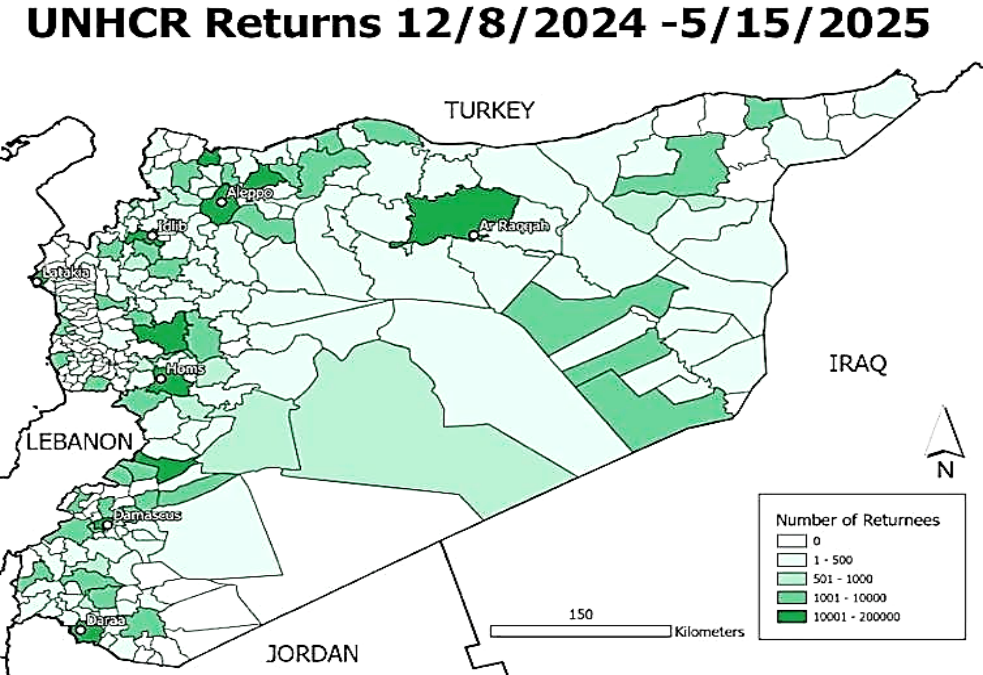

During that 14-year conflict some 06 million people fled Syria, mainly to neighbouring countries Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon but also to Europe. Astonishingly, around a quarter of those refugees returned home in 2025.

But what is driving their return and what conditions are they arriving back home to? Sandra Joireman, an expert in post-conflict return migration, explains that Syria post-war reconstruction is far from complete and violence against minority groups continues. Yet many refugees are opting to make the return journey home due, in part, to deteriorating conditions are hardening stances in host nations. Yet 14 year of conflict has created barriers to reintegration in Syria, homes and land registries have been destroyed, making it difficult for many to stake a claim over previous properties.

“Ultimately, a year after the civil war ended, Syrians are returning because of a mixture of hope and hardship: hope that the fall of the Assad government has opened a path home, and hardship driven by declining support and safety in neighbouring states”, Joireman writes, adding: “Whether these returns will be safe, voluntary and sustainable are critical questions that will shape Syria’s recovery for years to come”.

Close to 1.5 million Syrian refugees have voluntarily returned to their home country over the past year. That extraordinary figure represents nearly one-quarter of all Syrians who fled fighting during the 13-year civil war to live abroad. It is also a strikingly fast pace for a country where insecurity persists across broad regions. The scale and speed of these returns since the overthrow of Bashar Assad’s brutal regime on December 08th, 2024, raise important questions: Why are so many Syrians going back, and will these returns last? Moreover, what conditions are they returning to?

As an expert in property rights and post-conflict return migration, Joireman have monitored the massive surge in refugee returns to Syria throughout 2024. While a combination of push-and-pull factors have driven the trend, the widespread destruction of property during the brutal civil war poses an ongoing obstacle to resettlement.

Where are Syria’s refugees?

By the time a rebel coalition led by Sunni Islamist organization Hayat Tahrir al-Sham overthrew the Assad government, Syria’s civil war had been going on for more than a decade. What began in 2011 as part of the Arab Spring protests quickly escalated into one of the most destructive conflicts of the 21st century.

Millions of Syrians were displaced internally, and about 6 million sought refuge abroad. The majority went to neighbouring countries, including Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon, but a little over a million sought refuge in Europe. Now, the European countries are struggling to determine how they should respond to the changed environment in Syria. Germany and Austria have put a hold on processing asylum applications from Syrians. The international legal principle of non-refoulement prohibits states from returning refugees to unsafe environments where they would face persecution and violence.

But people can choose to return home on their own. And the fall of Assad altered refugees’ perceptions of safety and possibility. Indeed, the U.N. refugee agency surveys conducted in January 2025 across Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq and Egypt found that 80% of Syrian refugees hoped to return home – up sharply from 57% the previous year. But hope and reality are not always aligned, and the factors motivating return are far more complex than the change in political authority.

Why are people returning?

In most post-conflict settings, voluntary return begins only after security improves, schools reopen, basic infrastructure is restored and housing reconstruction is underway. Even then, people often return to their country but not their original communities, especially when local political control has shifted or reconstruction remains incomplete.

In present-day Syria, violence continues in several regions, governance is fragmented, and sectarian conflicts persist. Yet refugees are returning anyway. A major factor is the deteriorating conditions in neighbouring host countries. Most of those who came back to Syria in the early months after Assad’s fall came from neighbouring states that have hosted large refugee populations for more than a decade and are now struggling with economic crises, political tensions and declining aid.

In Turkey, for example, Syrians have faced increasing deportations and growing structural barriers to integration, such as temporary status without the possibility of naturalisation and strict local policies of registration.

In Lebanon, meanwhile, recent violence and a steep drop in international assistance have left Syrian refugees unable to secure food, education and health care.

And in Jordan, international reductions in humanitarian support have made daily life more precarious for refugees. In other words, many Syrians are not returning because their homeland has become safer, but because the places where they sought refuge have become more difficult.

Although any data on the religious or ethnic makeup of returnees is unavailable, yet the patterns from other post-conflict settings suggest that returnees are usually from the majority community aligned with the new dominant political actors. After the war in Kosovo, for instance, ethnic Albanians returned quickly, while Serb and Roma minorities returned in much smaller numbers due to insecurity and threats of reprisals. If Syria follows this trajectory, Sunni Muslims may return in higher numbers, as the country’s president, Ahmed al-Sharaa, led the Sunni rebel coalition that overthrew Assad.

Syrian minority groups, including Alawites, Christians, Druze and Kurds, may avoid returning altogether. Violent incidents targeting minority communities have underscored ongoing instability. Recent attacks on the Alawite population have triggered new waves of displacement into Lebanon, while conflicts between Druze militias and the government in Sweida, in southern Syria, have led to more displacement within the country. These episodes illustrate that while pockets of the country may feel safe to some, instability persists.

There are barriers to return –

One of the most significant obstacles facing refugees who wish to return is the condition of their homes and the status of their property rights. The civil war caused widespread destruction of housing, businesses and public buildings.

Land administration systems, including registry offices and records, were damaged or destroyed. This matters because refugees’ return requires more than physical safety; people need somewhere to live and proof that the home they return to is legally theirs. Analysis by the conflict-monitoring group ACLED of more than 140,000 qualitative reports of violent incidents between 2014 and 2025 shows that property-related destruction was more concentrated in inland provinces than in the coastal regions, with cities such as Aleppo, Idlib and Homs sustaining some of the heaviest damage.

This has major implications for where return is feasible and where it will stall. With documentation lost, homes reoccupied and records destroyed, many Syrians risk returning to legal uncertainty or direct, and sometimes violent, conflict over land and housing.

Post-civil war reconstruction will require not only the rebuilding of physical infrastructure but also the restoration of land governance, including mechanisms for property verification, dispute resolution and compensation. Without all this, refugee returns will likely slow as people confront uncertainty about whether they can reclaim their homes.

Shaping Syria –

Whether the wave of returns throughout 2025 continues or proves to be a temporary surge will depend on three main criteria: the security situation in Syria, reconstruction of houses and land administration systems, and the policies of the countries hosting Syrian refugees.

But ultimately, a year after the civil war ended, Syrians are returning because of a mixture of hope and hardship: hope that the fall of the Assad government has opened a path home, and hardship driven by declining support and safety in neighbouring states.

Whether these returns will be safe, voluntary and sustainable are critical questions that will shape Syria’s recovery for years to come.

Team Maverick.

Bangladesh Votes for Change as BNP Surges Ahead in Post-Hasina Election

Dhaka, Feb 2026 :Vote counting began in Bangladesh late Thursday after polling concluded f…