“Reverse Migration After India’s Lockdown: Impact on Indigenous Communities”

Effects of Reverse Migration on Indigenous Communities following India’s Lockdown –

The Coronavirus pandemic posed a grave health threat to Indigenous peoples around the world. The threat has proven not only epidemiological, but also social and economic, as many countries imposed strict lockdowns that created additional burdens on communities already suffering from resource deprivation and marginalisation.

In India, indigenous communities—legally known as “Scheduled Tribes” or popularly termed “Adivasi” (“original inhabitant”) are highly dependent on performing migrant labour for subsistence. These community was highly vulnerable during India’s harsh lockdown, when over 1.5 crore people returned to their native villages from cities and industrial centres during this period, many suffering intense hardships along the way. However, there has been very little ethnographic engagement with the effects of the lockdown on the villages where the migrants returned during the lockdown.

While the government of India does not officially acknowledge any particular group as “indigenous”, the Constitution of India empowers the state to list certain communities as “Scheduled Tribes” based on “geographic isolation”, “primitive characteristics”, and “distinctive culture”.

Despite popular ideas that attributes indigenous villages in Schedule 5 areas (Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Rajasthan, and Telangana) as homogenous, they are comprised of different communities that have unequal access to resources.

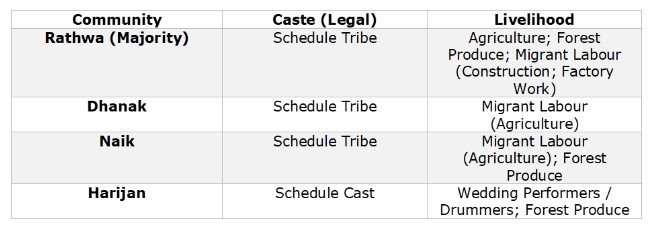

In Moti Sadli village in Gujarat, with a population of 3,279 there are four major communities:

- The Rathwa is the largest tribal community in the village and practice subsistence agriculture, and have rights to forest land. They are also relatively more educated than the other communities. Besides agriculture, some Rathwas travel to the cities of central and southern Gujarat (such as Ahmedabad, Vadodara, and Surat) mainly in search of construction work.

- Dhanaks and Naiks are indigenous groups that have no land, although the latter have some claims to the forest. These communities are less educated, and they often go to the fertile areas of western Gujarat to work as farm labours, where much of their salary is paid in kind from the season’s crop.

- The Harijan community are a Schedule Caste group who predominantly settle in the villages. Their income is generated from performing music at the weddings of indigenous communities and also from making and selling baskets and other items from collected forest materials such as bamboo. Their education level is comparatively lower.

The effects of the lockdown in Moti Sadli were distributed across the communities of the village in different ways:

- Many Rathwas who worked in the cities of Gujarat, which were most affected in the early wave of the pandemic, returned to the village. Several migrant laborers used this time to remodel their village homes. As the agricultural season had ended, there was some food available, although since markets were closed, surplus agriculture could not be converted to cash. As Rathwas had access to the forest, the community could also gather the flowers of the mahua tree (which was in blooming season), which is sold either raw or is distilled and sold as a beverage.

- Members of the Harijan community did not migrate for labour; their loss of livelihood came primarily from the shutting down of weekly markets (hat) where they sell their goods and the cancellation of weddings. They attempted to compensate for this by setting up exchanges in the local villages instead of market towns to circumvent lockdown restrictions.

- Members of the Naik and Dhanak communities are also landless but depend on migrant farm labour for their livelihoods. As a result, many did not return during the lockdown, instead choosing to stay in the fields where they worked and survive off their portion of the season’s harvest. Some, however, did return and their stories were more harrowing. For example, one Dhanak man recounted his family’s journey from western Gujarat, and how after they returned to the village, they had no more food left. He and his family traded seeds, which they had collected from their work sites, with merchants for food grains, and then managed to pool together enough food grains from community members and neighbours to stave off starvation.

The impact of the pandemical lockdown were manifold in the 5th Schedule villages of Gujarat and Jharkhand. In both cases, migrant workers had a difficult time returning home, and endured several hardships along the way. Once home, the social position of a particular community greatly conditioned the experience and possibility of self-sufficiency under the stringent lockdown conditions.

The dominant indigenous communities, such as the Ho of Jharkhand, and Rathwa of Gujarat, due to their access to land and natural resources could more easily weather the pandemic lockdown, while the landless indigenous communities and the formerly untouchable communities had to improvise in order to survive. Due to the closure of weekly markets, the communities emphasised localised forms of trade and a greater sense of dependence on the village community.

However, these strategies had their limits and could only provide sustenance for a limited period. As soon as lockdown conditions were lifted, there was a significant outflow of migrant labour back to their previous places of employment, contrary to reports from other parts of the country suggesting that migrants were more likely to stay in the villages.

In Gujarat, people had very little expectation that the government would provide alternative livelihoods for greater self-sufficiency, while in Jharkhand, there were some overtures made by the state government to promote local employment.

The findings revealed that indigenous communities could survive when cut off from the market economy; however, the conditions of survival differed due to unequal access to resources. It also showed that despite the special status of these areas, state development activities have been insufficient to curtail migration brought about by countervailing policies of resource extraction and agricultural degradation.

Impeccable policies emphasising local employment and skills generation such as that envisioned by the Jharkhand government are to be deplored & properly implemented across all the Schedule 5 areas of the country. In addition, policies also need to emphasise that all communities residing in these areas have access to sustenance and income either through agriculture or forest rights. Such policies could mitigate the overall survival burden during future crises.

Impact of Community based depression –

The devastated COVID-19 pandemic, declared on 11th. March, 2020, and the imposition of a nationwide lockdown on 25th. March, 2020 yielded to an extraordinary health, social and economic challenge, alongwith the impact on people’s mental health demonstrated to be catapulting.

The unpredictable nature of the disease, the loss of control & personal freedoms, the conflicting messages from authorities, sudden changes in plans for the immediate future, or concern for one’s own health and well-being and that of one’s relatives are examples of sources of stress associated with the outbreak of the pandemic. This has been followed by home confinement for indefinite periods and substantial and growing financial losses.

A recent systematic review on the psychological impact of previous epidemics such as Ebola, H1N1 influenza pandemic, Middle East respiratory syndrome and equine influenza found negative psychological effects including post-traumatic stress symptoms, anger and confusion. Factors such as long duration of quarantine, fears for infection, inadequate information, stigma, or financial loss were related to higher negative psychological impact. These major stressors can be expected to lead to an increased risk of psychopathology such as anxiety or depression.

Depression is a pervasive and costly illness with a lifetime prevalence of 15-20%. It is the fourth largest contributor to the global burden of disease, and the third largest source of years lost to disability. Depression is more prevalent among the poor significantly contribute to poverty and poverty traps.

For India it is immensely important to understand the economic impact of depression, and to identify effective and scalable treatments. Although the Mental Health Care Act of 2017 creates a legally binding right to mental health care in India, only 15% of people with depression in India receive care, since treatment options are limited by a shortage of providers.

The prevalence of depression has adverse economic impacts, treatment options in India are limited by a shortage of providers.

The writer has envisioned on the impact of providing community-based depression treatment to low-income adults, and has found that these community-based treatments improve mental health and schooling outcomes for older children, and reduces risk tolerance. Additionally, pairing pharmacotherapy (PC) with livelihoods assistance (LA) provides alluring relief at a lower cost.

To be continued…………………

Writer Suvro Sanyal

Mavericknews30 has launched a series of articles on community building, sharing insights and success stories. Stay tuned for the next article as we explore how to create stronger, more connected communities!

Log on : www.mavericknews30.com

Follows us on : Twitter @mavericknews30

YouTube : @MarvickNews30

Bangladesh Votes for Change as BNP Surges Ahead in Post-Hasina Election

Dhaka, Feb 2026 :Vote counting began in Bangladesh late Thursday after polling concluded f…